Geometry of Torque-free Motion and Nutation Angle Solution#

Explicit description of the inertia parameters coupled with the developments regarding the angular speeds from the previous section are sufficient to visualize the motion of the angular velocity vector from the body-fixed frame. However, it is also possible to visualize its motion in an inertially fixed reference frame which is the focus of this section. These developments are then used to study the variable mass cylinder problem in the following section.

Exploiting the fact that the variable mass system’s angular momentum vector is fixed in inertial space [Nanjangud, 2016, Nanjangud and Eke, 2018] enables us to visually study the angular velocity evolution from an inertial frame. The angular momentum of a general variable mass system can be written as

Retaining the assumption of steady and axisymmetric relative internal mass flow reduces Equation (34) to

With the definitions of \({\bf I}^*\) and \(\boldsymbol{\omega}\) from Equations (3) and (4), respectively, the component form of the angular momentum vector is

or

Using the component form of \(\boldsymbol{\omega}_{t}\) from Equation (31) in Equation (37) gives

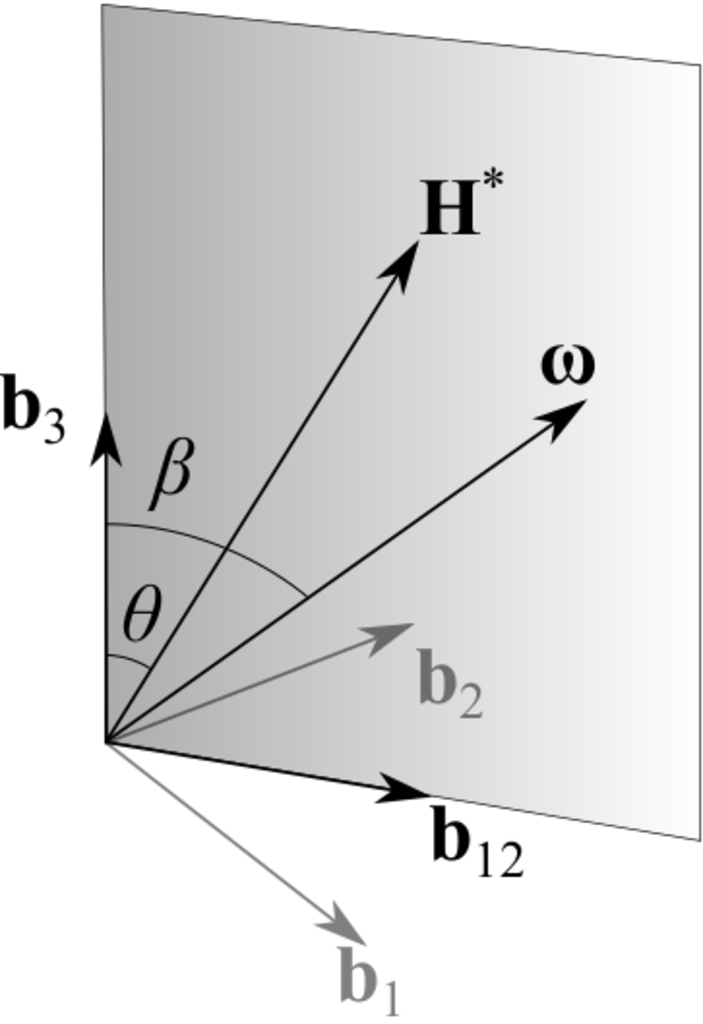

Equation (38) gives an alternate form of the angular momentum of an axisymmetric variable mass system. Axisymmetric rigid systems (of constant or variable mass) are unique in that their angular momentum and angular velocity vectors are always in the same plane, evident by comparing Equations (33) to (38); \({\bf H}^*\) and \(\boldsymbol{\omega}\) are in the same plane formed by \({\bf b}_{12}\) and \({\bf b}_3\) and this is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Geometry of motion setup of vectors.#

In this figure, \(\theta\) is the angle between \({\bf H}^*\) and \({\bf b}_3\), and \(\beta\) is the angle between \({\bf b}_3\) and \(\boldsymbol{\omega}\). These angles can be computed from the figure as

and

Evaluation of these angles \(\theta\) and \(\beta\) along with the solutions to the angular velocities permit a visual understanding of the motion of the body in both inertial space and the body-fixed coordinate system.

In the case of axisymmetric rigid bodies of constant mass, \(\Gamma = 1\) and the spin rate and inertia scalars are constant. Consequently, in Equation (39) and (40), both angles evaluate to constants and visualizing the motion of \(\boldsymbol{\omega}\) results in the formation of two cones: as it rotates about \({\bf b}_3\) and another as it rotates about \({\bf n}_h\), a unit vector parallel to the inertially fixed \({\bf H}^*\). The two cones are appropriately named the body cone and space cone, respectively.

In the case of axisymmetric variable mass systems, angles \(\theta\) and \(\beta\) are typically functions of time. The angles may grow or decay as dictated by the instantaneous values of the radii of gyration, \(\Gamma\), and the spin rate. It is also possible, in the case of the same variable mass system, for \(\beta\) to exceed \(\theta\) at certain instants while it may not at certain other instants. Fig. 2 represents an instant where \(\beta>\theta\), which occurs when \(k_3>k_1\). Also, \(\boldsymbol{\omega}\) does not trace cones as it rotates about \({\bf b}_3\) and \({\bf n}_h\). Thus, generic names are used for the surfaces it traces; in this document, they are referred to as the body surface and space surface (which reduce to the body cone and space cone for the limiting case of a constant mass rigid body, respectively).

In the spacecraft dynamics literature, \(\theta\) is referred to as the nutation angle [Kaplan, 1976]. In classical mechanics, \(\theta\) may also be identified as the second Euler angle [Likins, 1973] and, thus, Equation (39) also gives the solution to said Euler angle. Growth in nutation angles results in a coning motion which is undesirable in spacecraft. Potential hazards of excessive nutation or coning motion might be poor initial conditions for subsequent mission operations, or possible loss of communications with a spacecraft due to incorrect pointing between its antenna and the base station. One such case of excessive nutation growth was observed in missions powered by the STAR-48 SRM [Cochran and Kang, 1991, Flandro et al., 1987, Halsmer and Mingori, 1995, Meyer, 1983, Mingori and Yam, 1986, Or, 1992]. To mitigate this growth, an active nutation damper is used in these missions [Webster, 1985].

Closed form expressions to \(\theta\) are available when the angular speeds are themselves available in closed form. These closed-form expressions are invaluable to not only evaluate stability but also for appropriate control strategy formulation to temper any instabilities. Solutions to the angular speeds are derived in the next section for a special class of variable mass systems: the axisymmetric variable mass cylinder. These closed form solutions are then utilized in constructing the body and space surfaces. The choice of cylindrical systems as an idealization is based on their use in several prior studies on rocket flight; Snyder and Warner [Snyder and Warner, 1968] and Eke et al. [Eke et al., 2004, Eke and Wang, 1995] are some examples of investigators who have incorporated cylindrical propellant grains in their studies on the attitude motions of variable mass space vehicles.